Peatlands at COP26

– By Lorna Harris –

Our planet is warming, and this will have profound impacts on ecosystems and the species that depend on them, including us. This was one of the main messages of the new IPCC report, published in February 2022. The risk to high-carbon ecosystems and the potential amplification of global warming resulting from the release of greenhouse gases (GHG) from these ecosystems was highlighted, particularly for peatlands. Peatlands cover only 3% of the Earth’s surface but are one of the largest terrestrial carbon stores on the planet, with around 25 to 30% of the global soil carbon stored as partially decayed organic matter in deep peat soils. Protecting and maintaining the peatland carbon sink and the stability of stored carbon is internationally recognised as an essential action to help mitigate global climate change.

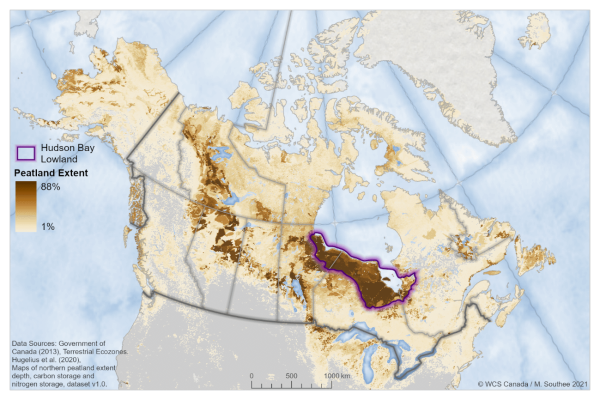

The need to protect mostly intact peatlands across Canada for both the climate and biodiversity crises was one of the key messages presented at COP26 by Dr Constance O’Connor and Dr Justina Ray from the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) Canada, Dr Lorna Harris from the University of Alberta and WCS Canada, and Vern Cheechoo from Mushkegowuk Council. They shared the findings of a collaborative paper by Dr Lorna Harris and peatland researchers from across Canada, published in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. One-quarter of the world’s peatlands are in Canada (Map), yet only ~10% are within protected areas and there are very few policies to protect peatlands from economic development and infrastructure. The paper describes the science and policy instruments and tools needed to protect these vast peatland carbon stores, as once lost through land conversion, the carbon is “irrecoverable” in that it cannot be recovered by 2050, as required for net-zero global emissions.

At the COP26 event, the team highlighted the Hudson Bay Lowlands (photo) – one of the largest remaining intact peatland complexes in the world that stores around 30 to 35 billion tonnes of carbon, which is close to three years of annual global GHG emissions and around 175 years of Canada’s current annual GHG emissions. Dr Harris described the threats to peatlands across Canada, including mining and infrastructure development in the Hudson Bay Lowland, and Dr Ray highlighted the particular risk of increased interest in the extraction of ‘critical minerals’ in this region, mainly in the so-called ‘Ring of Fire’ development. Vern Cheechoo described the importance of the Hudson Bay Lowlands as a homeland for Indigenous Peoples and shared the knowledge and insight of First Nations living in the region of the impacts of global climate warming and environmental change on the connected forests, peatlands, and rivers. Vern highlighted the relationship of Indigenous People to the land and waters of the region, and the important connection to the land – “that we are the land, we are the animals, we are the environment, and therefore whatever we are doing to the land, to the territory, we are doing to ourselves.”

Targeted policies from local to global scales are urgently needed to protect the vast peatlands of Canada, for their massive carbon stores and global climate regulation, for biodiversity, and for their social and cultural importance as the homelands of Indigenous Peoples.

Dr Lorna Harris serves as Forests, Peatlands, and Climate Change Scientist at Wildlife Conservation Society Canada. Lorna is an ecosystem scientist, working to understand the ecology, hydrology and biogeochemistry of peatlands and forests in North America’s boreal zone. Lorna’s research focuses on how peatlands form and develop over time, and how this development may be impacted by environmental change, either due to global climate warming, or direct disturbance such as infrastructure development for resource extraction. Lorna is also working on improving links in science and policy for the better protection and management of peatlands across Canada.