Turning Your Passion into a Career

– By Francis Lavigne-Theriault –

To say that I have never followed a predetermined path is an understatement. Much like most of my peers, I had an interest in weather from a very young age. Being born in Montreal and living through the great ice storm of 1998, my interest for extreme weather events was sparked early in my life. Shortly after this historic event, I moved to the east coast of Canada and grew up in New Brunswick. There, my passion for weather really grew. The east coast is notorious for Nor’Easter and post-tropical cyclones, and I would always enjoy going outside or looking out the window to witness these extreme weather events. Snow days were spent outside. I would build a fort in metre-high snow drifts and spend hours outside in the worst part of the storm. My mother would worry, sometimes watching me out of the window, making sure I stay within eyesight. Little did I know, this type of activity would mirror my current storm chasing methodology except I now choose the luxury of a cozy four-wheel drive vehicle. My dad would often feed my weather-passion by bringing me all the weather books he could find. The best Christmas gifts I’ve ever received and the only ones I remember from my childhood, were weather books, some of which I still own today. When we moved back to Quebec in my mid-teens, I remember having a TV in my room. I would run The Weather Network on a 24/7 loop. It was my main source of weather information and it continued to fuel my passion for weather. I remember watching forecasters covering blizzards, winter storms and severe storms in the field and kept thinking it was amazing that you could get paid doing that.

Throughout high school, I wasn’t much of a weather nerd, and I’ve always despised math courses. University was never a path I envisioned, being more of a practical man, I could see myself being more into trades, rather than academia. However, sometimes things just have a way of working out, and the University of Manitoba called out to me in 2013. The geography program offered a storm chasing course, where you could essentially get credits for learning how to chase storms. This was very appealing for me, especially since I believed theory and books weren’t as practical as learning things in the field and witnessing them firsthand. Looking back now, I can only sit here and laugh considering I never ended up taking the course! In winter of 2013, I started my first semester at the U of M, there I witnessed my first Prairie blizzard, and I was hooked (Fig. 1).

There was no doubt in my mind that Manitoba was where I needed to be. After several long years of hiatus, my weather passion was reignited in a lonesome Winnipeg basement I was renting out for the term. It was there, that I began making plans for my first storm chasing trip to the United States in spring of 2013. I spent most of that term watching and reading everything I could find on storm chasing and severe weather forecasting. From the Discovery show Storm Chasers, to university textbooks, to peer-reviewed publications, I read and watched it all. Once I felt confident I could do this myself safely, I began preparations for a May 2013 storm chasing adventure to the United States. This trip sparked a life-long obsession with tornadoes and supercell thunderstorms.

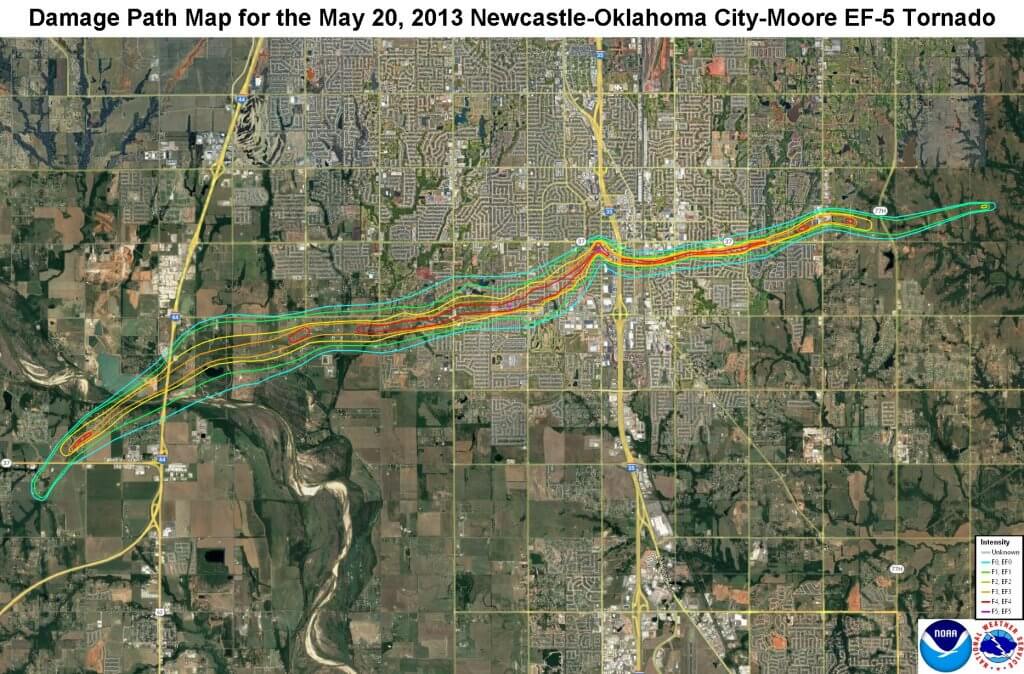

A friend and I spent most of May driving around the U.S. Southern Plains in search for tornadoes without much success. Out of the two weeks we had spent there, we had only seen one tornado so far. We were ill equipped, with only a laptop and a cellphone, which didn’t have roaming capabilities. We would get our weather information from the Storm Prediction Center and various other online sources in the morning at our hotel or by using McDonald’s WiFi. However, the last two weeks of May presented a classic trough ejection over the Plains, which meant tornado outbreaks were likely. On May 20th, we sat in Moore, OK, waiting for storm development. A classic dryline was expected to trigger storms just west of Oklahoma City. It wasn’t long after lunch that storms began developing quickly. One storm in particular seemed promising on radar. By the time we headed down to Newcastle, the storm was tornado-warned. We positioned ourselves just south of the rotating wall cloud (Fig. 2) and watched a cone-shaped funnel cloud come down.

It was beautiful and exciting, but also frightening as it was headed straight for Moore. We watched in awe and disbelief as the tornado became wider and wider and destroyed entire neighbourhoods. This tornado was later rated EF5 with estimated 340 km/h winds. The tornado was on the ground for approximately 40 minutes, travelled for 22.5 km, caused 24 fatalities and 212 injuries (National Weather Service, 2023). This event still haunts me to this day and became a capstone event that would inspire a decade of storm chasing and field work on supercell storms. Every single moment of my life and every single dollar from this moment on would be dedicated to excelling at storm chasing, severe weather forecasting and in the field logistics.

Fast-forward to 2021, when I was offered a full-time research assistant position with the Northern Tornadoes Project (NTP) at the University of Western Ontario (https://www.uwo.ca/ntp). My position involved helping with post-event damage surveys across Canada to assess wind damage and estimate wind speeds using the Enhanced Fujita Scale. This was a dream come true! Another part of my job was conducting French and English media interviews to promote awareness of the project to all Canadians. Over the years, my job functions varied, and I’ve enjoyed the diverse nature of the work. From working on updating Canada’s national tornado database to leading surveys (Fig. 4) to presenting at a national and international conference.

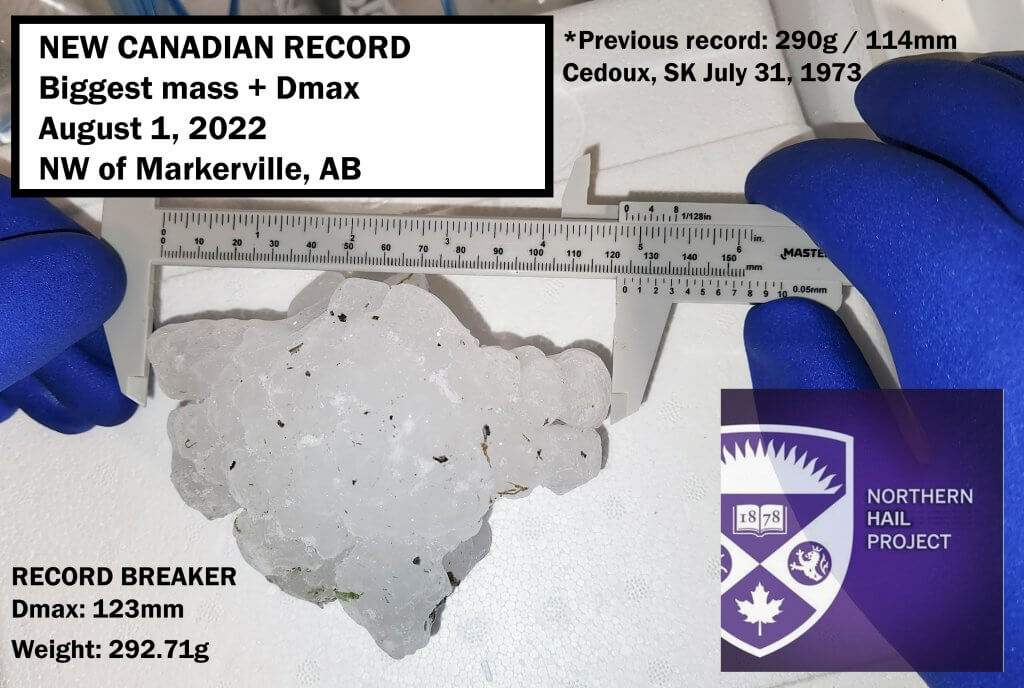

In spring 2022, I was offered the opportunity to work with the newly formed Northern Hail Project (NHP) as their first field coordinator (https://uwo.ca/nhp). My 11 years of storm chasing experience and field logistics were going to be put to good use!

As the field coordinator, I organised and led a small team of students in Alberta, under the supervision of the Executive Director, in the collection of hail directly behind intense thunderstorms including supercell storms. This was a no-brainer for me, having done over 300 000 km over the last 11 years chasing storms across North America, but I was very excited to put my expertise to conduct field research on severe storms. The pilot year of the NHP was very successful; the field team was able to retrieve a hailstone on August 1st near Markerville, AB that broke the previous 1973 record for size and weight (Fig. 5). After the successful field campaign, I returned home to Ontario with another chasing season under my belt and was offered an opportunity to do a master’s degree at Western with the NHP to continue the work I have been doing.

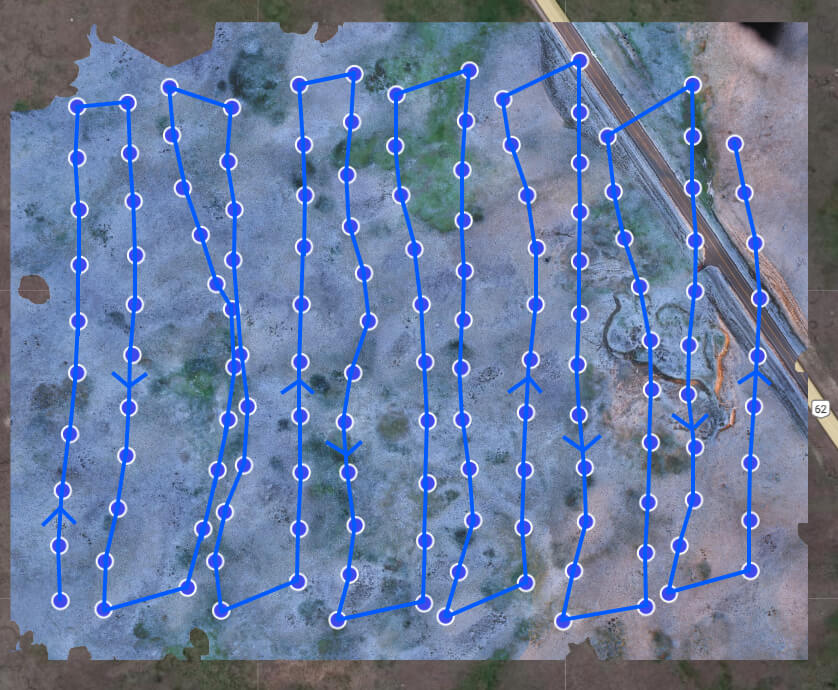

In May 2023, I officially began a Master’s in Engineering Science at Western. My master’s topic involves using the latest in drone technology to capture the spatial characteristics of hail swaths across Alberta. Therefore, in summer 2023, I spent another summer in Alberta with the NHP team collecting data, but this time for my thesis. Fig. 6 shows a hail swath across the foothills of Alberta in 2022 from a UAV. These are the types of case studies I was trying to capture in 2023 for my thesis work. To do so, we would drive across the hail swath from north to south and do a transect to determine the width of the swath from the ground and from the air using UAVs. Another ground team would collect hail within the swath and try to find the west to east extent of it.

These combined datasets will enable us to make the first comprehensive case study of a hail swath while hail is still on the ground using both ground observations and UAV imagery. Fig. 7. shows an example of a processed orthomosaic map, which combines UAV imagery and stitches it into a georeferenced map.

The next steps will be to combine the data and comment on the efficiency of the different UAVs used during the campaign and develop methodologies for the collection of data directly after hailfall using UAVs as well as do an in-depth meteorological analysis case study of one of our greatest hits from the 2023 campaign.

Francis Lavigne-Theriault (BA [Hons] ’21, Geography and Certificate in GIS & Remote Sensing, York University) has spent more than a decade chasing storms across North America, developing his severe weather forecasting skills, and becoming an expert on communications, social media and in-the-field logistics. In addition to working part-time with the NTP as a bilingual Research Assistant, Francis has embarked on graduate studies at Western Engineering with the newly formed Northern Hail Project (NHP). His Master’s degree research focuses on capturing southern Alberta hail swaths with cutting-edge drone technology.

References

National Weather Service. (2023). The Tornado Outbreak of May 20, 2013. Retrieved from https://www.weather.gov/oun/events-20130520.

career, Francis Lavigne-Theriault, hail, Northern Hail Project, Northern Tornadoes Project, storm, tornado, University of Western Ontario