The Great Smoke Pall of 1950 and Other “Dark Days” that have Blanketed Eastern North America

– By Kevin Hamilton –

The extraordinary 2023 Canadian wildfire season has been in the public eye for much of this spring, but during June 7-8 the event entered a new phase of global media attention as extremely smoky conditions were experienced in the major population centers in the eastern US. On June 7 a headline in the Washington Post read “It looks like Mars outside: Smoke engulfs East Coast, upending daily life.” Then on June 8 among the many smoke-related headlines in the Washington Post were: “The East Coast can’t breathe – and more wildfires are coming” and “On the East Coast, residents don masks, cancel outdoor activities”, and in the New York Times: “Wildfires spread smoke, and anxiety, across Canada to the US”.

The weather in the month of May in western Canada was dominated by a persistent heat dome leading to favorable conditions for the initiation and spread of wildfires. According to Dave Phillips of Environment Canada “in western Canada, this May was the warmest and driest on record” (see also this summary of May 2023 mean conditions). Then, according to Owens (2023), the proximate cause of extreme smoke conditions on June 7-8 in the eastern US was “a large low-pressure system […] sitting over Maine for several days. The system […] block[ed] transport of the smoke to the east, while the system’s counter-clockwise winds […] act like a conveyor belt, dragging the smoke south to the eastern seaboard”.

An Unprecedented event?

There have been claims in the media and by government officials, including New York City Mayor Eric Adams, that the effects in the eastern US were “unprecedented”. The word unprecedented indeed was used in the headlines of several media stories at the time.

A relevant new scientific result was quickly produced to characterize the health effects of the wildfire pollution in the June 7-8 period. The Environmental Change and Human Outcomes group at Stanford University computes a 10 km resolution daily gridded analysis of a standard measure of air quality due to particulates (specifically PM2.5) from wildfire smoke over the contiguous US. Convoluting this analysis for individual times with a high resolution map of population density in the US produces an estimate of the integrated effect of wildfire smoke on human health in the US. By the morning of June 10, the Stanford group published their results on Twitter showing that June 7th (8th) was the worst day (second worst day) on record. This detailed result supports the notion that the June event in the US was unprecedented, but their analysis was limited to after 2005 because it relies on a NOAA smoke plume product which is only available starting in 2006.

While the degree of widespread smokey conditions over eastern North America seen now in early June 2023 is unprecedented in most people’s memory, without longer records of detailed observations across the country it is difficult to know precisely how the extraordinary conditions in June 2023 compare with past events.

Famous “Dark Days” in Eastern North America

History actually records very occasional eastern North American “dark days” in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries that clearly made great impressions on the populace at the time. Two memorable 19th century events notable for their widespread extent in Ontario and Quebec, as well as throughout New England, occurred on November 8, 1819 and September 5, 1881. Contemporary reports suggest that the daytime darkness in some locations was severe enough to be compared to night and led to candles being lit. These events have been described in articles published long ago in the now-defunct CMOS magazine Chinook by Scott Somerville and by the present author. A feature of the reports of these events that appeared in the newspapers of the time is the degree of anxiety that much of the populace felt, with concerns that the sky conditions were a prelude to “the end of the world”. In these cases the source of the sky-filling smoke was presumably wild fires in some remote western regions of North America, but there was a lack of actual knowledge of the fires. The mysterious nature and unexpected arrival of the sky phenomena likely fed the anxious concerns of the populace during these “dark days”.

The Great Smoke Pall of 1950

In the 20th century it seems the closest analogue of the recent wildfire smoke pall event occurred in late September 1950 when nearly the entirety of eastern North America experienced “dark days” resulting from wildfires in western Canada. A review of that event, referred to as “the great smoke pall of 1950”, provides some context for the remarkable conditions observed in early June 2023.

In the New York Times the first reference to the 1950 smoke pall was in a front page story on September 25 headlined “Forest fires cast pall on Northeast: Canadian drift 600 miles long darkens wide areas and arouses ‘atom’ fears”. According to the story a:

“… blanket of smoke from smoldering Canadian fires cast an awesome pall over parts of the Northeastern United States yesterday, causing consternation in countess communities as day turned into night. The smoke blanket, which plunged New York City into an eerie twilight in the early afternoon, swept across the Canadian border like a great shroud. It blotted out the sun in many places; in others, it turned the sun’s rays into a patchwork of brilliant purple, pink and yellow colors. Residents of Detroit, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Buffalo and other cities and towns in the path of the smoke blanket deluged police and newspaper telephone exchanges with calls for explanations of the phenomenon. Some worried folk thought there had been an atomic explosion. Some saw in the pall a sign of the world’s end.”

It is interesting that even as late as 1950 an intense popular anxiety from the appearance of the dark sky was widely felt, although it had a new contemporary feature in the concern about possible atomic explosions – the first Soviet atomic bomb test had taken place in August 1949. Of course, there was no satellite surveillance of the earth in 1950, but, compared to the 19th century, there was more capacity for information about remote fires to propagate quickly. In fact by the end of the day on the 24th the explanation for the dark skies in the eastern US was known; quoting again from the New York Times story:

“An official explanation came late in the day from the Weather Bureau in Washington. It said the smoke originated from a series of smoldering fires in the forests of Northern Alberta and the District of Mackenzie In Canada. […] A Canadian Press dispatch said the smoke drifted over the Province of Ontario in the morning, rising as high as 17,000 feet. The dispatch reported that the Alberta fires were burning through hundreds of acres of scrub timber 340 miles northwest of Edmonton.”

The New York Daily News published a story on the 25th reporting on some details of the previous day’s events when smoke

“spread across the Midwest and caused a heavy overcast, which occasionally amounted almost to darkness through the metropolitan area […] At Laguardia Field it was disclosed that many planes in the affected area had to fly by instrument…”

The United Press wire service had a story on the 25th including more description:

“The weird pall of smoke spread alarm across thousands of square miles in the US and Canada during the day. In Ohio chickens and birds roosted in the afternoon. In southern Ontario some persons […] believed an atom bomb had fallen and a Third World War had started. In Pittsburgh and Cleveland day baseball games were played under lights.[…]In Pennsylvania it was so dark street lights were turned on in many towns.”

Extraordinary Eyewitnesses

We are fortunate in having personal records of the impression made by the 1950 smoke pall in the writings of two sophisticated scientists of the time. The prominent Canadian astronomer Helen Sawyer Hogg (Fig. 1) and the prominent American meteorologist Harry Wexler were witnesses of the effects in Toronto and Washington, D.C. respectively.

Hogg wrote a monthly column in the Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada and her December 1950 column referred to people in Ontario being “startled on September 25 at a brief glimpse of the sun as a pale, bluish-mauve disc. At the same time the western sky became a dark, terrifying mass of cloud and haze […] The darkness was so marked at 3:30 in the afternoon that the writer observed a group of six wild ducks going to sleep quietly in the middle of the pond.” Hogg returned to this subject in her column 15 years later writing that “Anyone who witnessed, as I did, the great smoke pall of September 1950 can never forget the eeriness of the occurrence and the extraordinary gloom.”

Wexler (1911-1962), who was then head of research at the US Weather Bureau, wrote an article about the smoke pall that appeared in the December 1950 issue of the magazine Weatherwise. He noted the event was exceptional in featuring a “high concentration of smoke that so obscured the sun that it was visible to the naked eye without discomfort”. He also noted the extraordinary “violet and lavender color of the sun, and to a less extent, of the moon..”.

The Synoptic Situation

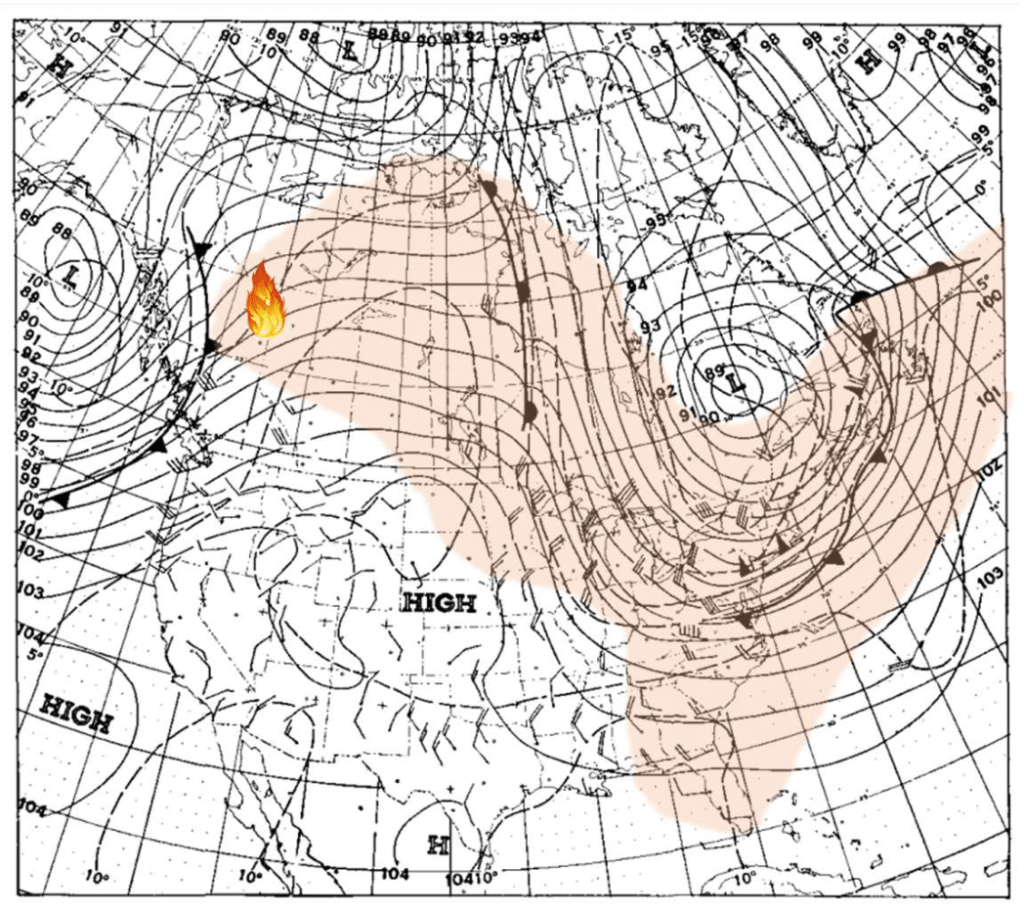

Wexler’s 1950 article reports on his investigation of the extent of the smoke coverage. He queried the experiences at 384 weather stations in the US and combined these with “synoptic reports” from the Canadian weather authorities and concluded that the “smoke covered the north central states, the Great Lakes region, New England, and the Atlantic coastal states as far south as Florida and inland as far west as northeastern Illinois, Kentucky, eastern Tennessee and Alabama. [although] the exact boundaries are uncertain”. Wexler also noted that on subsequent days there were reports of the smoke pall in Europe. In Fig. 2 I have denoted with colored shading Wexler’s estimated maximum smoke coverage area.

Of course, 1950 was before the deployment of artificial satellites and before the invention of lidar, so the capacity to monitor smoke plumes then was much inferior to that available today. However, simple ground based measurements of solar flux can provide some information on the aerosol column. While the Canadian historian of science W.E.K. Middleton remarked in his 1953 edition of his book “Meteorological Instruments” that equipment measuring the solar illumination at the surface was “not very commonly used in meteorological service”, in 1950 such measurements were apparently being taken regularly at about 50 US Weather Bureau stations. Wexler notes that at Buffalo, New York, “because of the presence of both smoke and clouds, the illumination from 1400 to 1600 EST on the 24th was comparable to pre-dawn or twilight.” At Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, “also with clouds and smoke on the 24th, the insolation dropped to […] less than one percent of the normal clear weather value.”

One notable feature of the smoke pall, at least as it initially spread over the eastern US, was its confinement in a layer well above the ground. Wexler notes that “many reports by airline pilots of the heights of the bottom and top of the smoke were received. Although these values varied to some extent, it seems likely that the smoke observed in the eastern US was largely confined to a layer whose base was at 8,000 feet and whose top was at or above 15,000 feet. No smoke was observed at the ground in this area; in fact the horizontal visibility was generally unlimited throughout the entire period.”

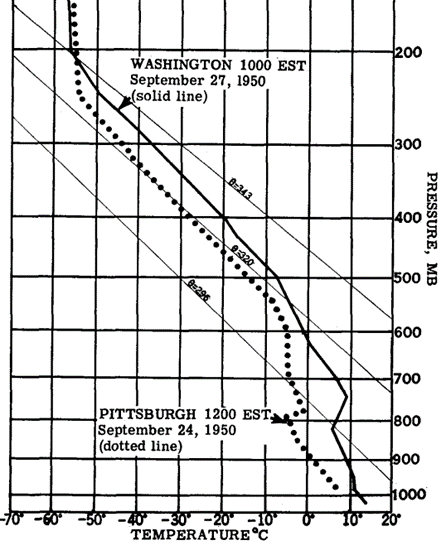

Clarence Smith, a US Weather Bureau meteorologist, also quickly wrote a more detailed examination of the synoptic situation associated with the 1950 smoke pall and published it in Monthly Weather Review. Smith notes that “The weather in British Columbia and Alberta was unseasonably warm and dry during the first half of September, contributing materially to the onset of extensive forest fires.” Later in the month the smoke from the fires streamed into the eastern US as a developing cyclone brought strong southward winds (Fig. 2). The Arctic air advected into the US displayed a strong inversion near 800 hPa on the 24th (Fig. 3) which helps explain why the thick smoke in the midtroposphere did not mix down to the ground.

With what must have been a large effort using hand calculation, the meteorologists in the US Weather Bureau calculated some isentropic back trajectories for a level within the smoke plume (potential temperature 312K) and were able to directly connect the smoke that arrived over Washington D.C. on September 24th with the region of the intense fires in Alberta more than 50 hours earlier. This presumably represents one of the earliest applications of this sophisticated technique to investigate long range atmospheric transport.

Conclusion

The heavy smoke pall overlying much of the eastern US on June 7-8, 2023 was an extraordinary event and almost certainly unmatched in this region by other events within most people’s memory today. However, this very recent event can be considered in a larger context and, in fact, widespread reports of intense “dark days” in the region appear occasionally in the historical record. The “dark days” of the 18th and 19th centuries are recorded purely as anecdotal reports of the sky appearance and other subjective measures of air quality. The “great smoke pall” of September 1950 is more fully documented through systematic meteorological measurements than the earlier dark days, but there are still not enough data for a direct quantitative comparison of the intensity of the 1950 event with that in June 2023.

Kevin Hamilton is Emeritus Professor of Atmospheric Sciences and retired Director of the International Pacific Research Center (IPRC) at the University of Hawaii. He has had a long career in academia and government including stints at McGill and the University of British Columbia in the 1980’s. His main research interests have been in stratospheric dynamics and climate modeling, but he has also investigated aspects of the history of meteorology. He currently serves as an Editor of the journal History of Geo- and Space Sciences.

Eastern North America, fire, historical, kevin hamilton, The Great Smoke Pall, wildfire smoke, wildfires